The First Navajo Hogan Book

A “flip” book in English and Diné Bizaad.

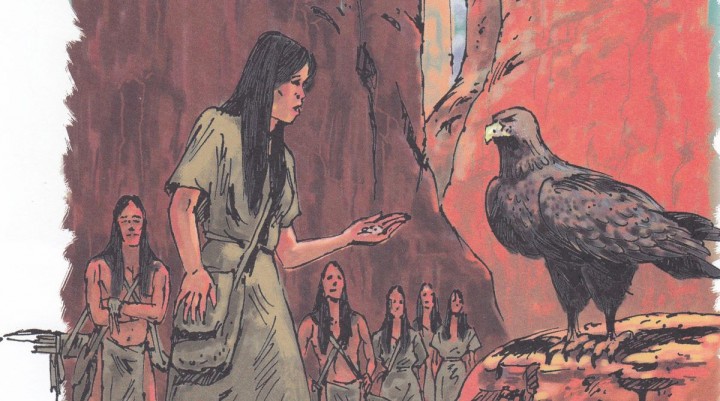

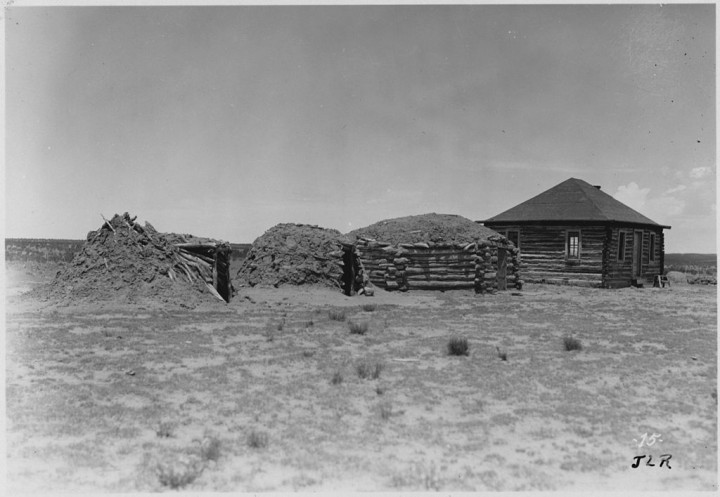

The Story of the First Hogan (Áltsè Hooghan), is a 38 page, bilingual “flip” book with beautiful, full-color illustrations by Charles Yanito. Story is told by Don Mose, Jr. This is a “perfect-bound” book, measuring 8.5 x 11”. The story tells how the animals helped First man and First Woman discover the type of shelter or dwelling that they needed for a home.

Readers accompany First Man and First Woman on a journey to discover the ideal type of dwelling for the Navajo People. First Man and First Woman find inspiration and insights as to how to design a home for themselves and future generations, by visiting the homes of their animal neighbors.

This paperback book contains 20 pages and is realistically illustrated with original paintings created by Navajo artist, Charles Yanito.

The Story of the First Hogan is a traditional narrative as told by Don Mose, Jr.

38 page, bilingual “flip” book “perfect-bound” measuring 8.5 x 11

Price $10.00

Ordering Information

San Juan School District

Heritage Language Resource Center

28 West 200 North

Phone: 435-678-1230

FAX: 435-678-1283

Store Hours: 9:00 – 4:30

Monday through Thursday

Email: rstoneman@sjsd.org

Online order at this Website: media.sjsd.org

We accept purchase orders, credit cards, and checks.

We bill only for items shipped and actual cost of shipping.

Personal orders ship after payment is received.

Please estimate 10% of purchase total for shipping cost.