In the world below there was no sun and no moon, and therefore no light, yet vegetation in innumerable forms and the animal people thrived. Among the latter were Gray Wolf people, Mountain Lion, Badger, Locust, Pine Squirrel, and Blue Fox, Yellow Fox, Owl,Crow, Buzzard, four different varieties of the Hawk people, and many others.

Their world was small. At its eastern rim stood a large white mountain, and at the south a blue one. These formed the home of First Man. A yellow mountain in the west and a black one in the north harbored First Woman. Near the mountain in the east a large river had its source and flowed toward the south. Along its western bank the people lived in peace and plenty. There was game in abundance, much corn, and many edible fruits and nuts. All were happy. The younger women ground corn while the boys sang songs and played on flutes of the sunflower stalk. The men and the women had each eight chiefs, four living toward each cardinal point; the chiefs of the men lived in the east and south, those of the women in the west and north. The chiefs of the east took precedence over those of the south, as did those of the west over those of the north.

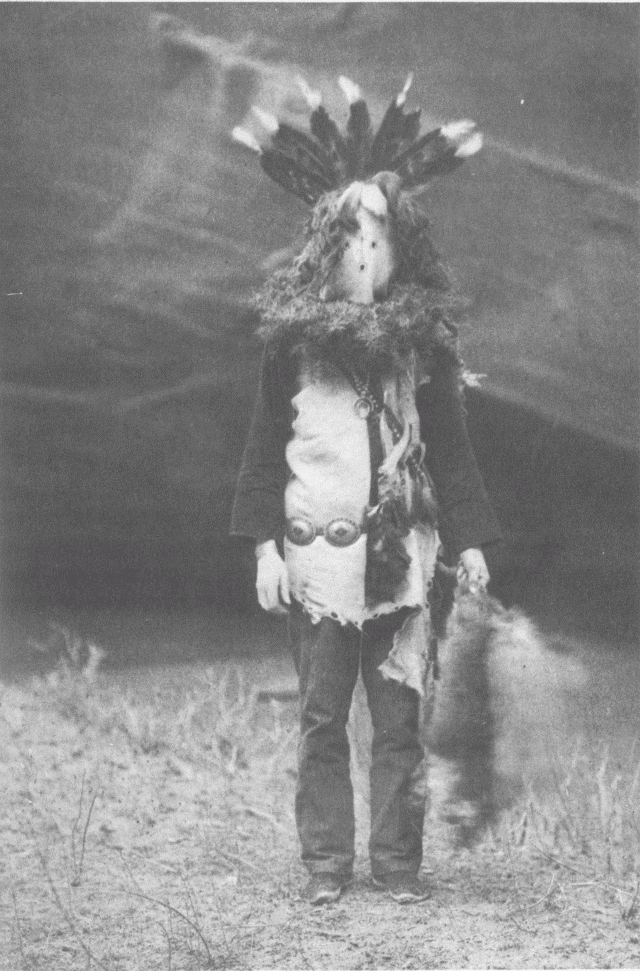

Navaho Talking God

This, the Talking God, is the chief character in Navaho mythology. In the rites in which personated deities minister to a suffering patient this character invariably leads, carrying a four-piece folding wand, balÃl, and uttering a peculiar cry.

As yet there was neither sun nor moon to shed light, only dawn, circling the horizon in the four colors ”white in the east, blue in the south, yellow in the west, and black in the north. Deeming it necessary that they should have light to brighten the world, and warmth for the corn and the grass, on their return to the earth’s center one of the chiefs made a speech advocating the creation of a sun and a moon.

First Man and First Woman placed two sacred deerskin’s on the ground as before. On the buckskin a shell of abalone was placed, on the doeskin a bowl made of pearl. The shell contained a piece of clear quartz crystal, and the bowl a moss agate. The objects were dressed respectively in garments of white, blue, yellow, and black wind, and were carried to the end of the land in the east by First Man and First Woman. With their spirit power and sent both the shell and the bowl far out over the ocean, giving life to the crystal and the agate as they did so, directing that the one who would be known as the Sun, should journey homeward through the sky by day, shedding light and warmth as he passed; the other, the Moon, must travel the same course by night. To each were given homes of turquoise in the east and west, and none but the Winds and the gods, and were to visit them.