The medicine-men, who are termed singers, hatáli, are a dominant factor in the Navaho life. Like all primitive people, the Navaho are intensely religious, and the medicine-men, whose function it is to become versed in the mysteries of religion, are ever prone to cultivate in the minds of the people the belief that they are powerful not only in curing disease of mind and body but of preventing it by their incantations. Anyone who possesses the requisite ability may become a medicine-man, but owing to the elaborate ceremonies connected with their practices it requires long years of application ere one can attain sufficient knowledge to give him standing among his tribesmen.

To completely master the intricacies of any one of the many nine days’ ceremonies requires close application during the major portion of a man’s lifetime. The only way a novice has of learning is by assisting the elders in the performance of the rites, and as there is little probability that opportunity will be afforded him to participate in more than two or three ceremonies in a year, his instruction is necessarily slow.

The medicine-men recognize the fact that their ritual has been decadent for some time, and they regard it as foreordained that when all the ceremonies are forgotten the world will cease to exist.

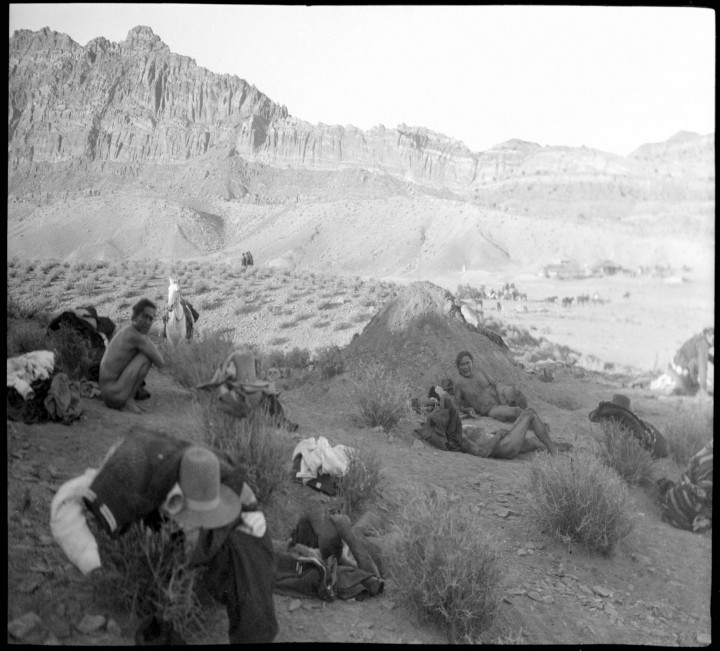

Hástin Yázhe (Navaho)

Photograph 1904 by E.S. Curtis

The most pronounced dread manifested by the Navaho is that derived from their belief respecting the spirits of the dead. It is thought that the spirit leaves the body at death and travels to a place toward the north where there is a pit whence the gods and the animals emerged from an underworld before the first Navajo were created, and which the dead now enter.

Their myths tell of the disappearance of a beautiful daughter of one of the animal chiefs on the fourth day after the gods and the animals came up into this world; diligent search was unrewarded until two of the searchers looked down through the hole and espied her sitting beside a stream in the lower world combing her hair. Four days later death came to these searchers, so that now the Navaho will go to any extreme to avoid coming into contact with spirits of the dead, chinde, which they believe travel anywhere and everywhere at will, often doing evil, but never good. The body is prepared for burial previous to death, and is never touched afterward if it can be avoided.

To the end that the spirit may begin aright its journey to the afterworld, the body is taken out of the hogan through an opening specially made in the wall on the northern side, for the doorway always faces the east. The immediate relatives of the deceased avoid looking at the corpse if possible. Friends of the family or distant relations usually take charge of the burial. A couple of men dig a grave on a hillside and carry the body there wrapped in blankets. No monument is erected to mark the spot.

Before the body is taken out, the hogan is vacated and all necessary utensils are carried away. The two men who bury the remains of the former occupant carefully obliterate with a cedar bough all footprints that the relations of the deceased may havemade in the hogan, in order to conceal from the departed spirit the direction in which they went should it return to do them harm.

The premises are completely abandoned and the house often burned. Never will a Navaho occupy a hogan, and when travelling at night he will take a roundabout trail in order to avoid one. Formerly horses were killed at the grave. So recently as 1906 a horse was sacrificed within sight of a Catholic mission on the reservation, that its spirit might accompany that of a dead woman to the afterworld. This horse was the property of the woman, and her husband, fearing to retain it, yet not daring to kill it himself, called upon another to do so.